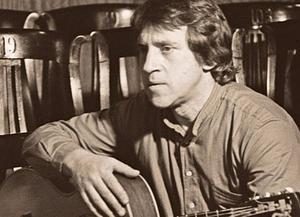

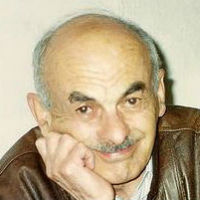

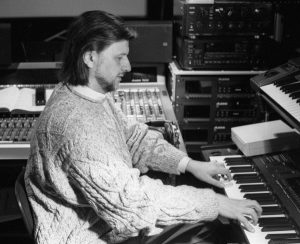

Alexey Rybnikov: “We will see revival in music”

The head of the Union of Composers of Russia, Alexei Rybnikov, told the portal Kultura.RF, what distinguishes the work of a musician in film and theater, how they will support talented graduates and why the melodies reflect what is happening in the world.

The head of the Union of Composers of Russia, Alexei Rybnikov, told the portal Kultura.RF, what distinguishes the work of a musician in film and theater, how they will support talented graduates and why the melodies reflect what is happening in the world.

– Alexey Lvovich, in May of this year you became the head of the Union of Composers of Russia. How did this happen?

– The fact that in the Union of Composers came some anarchy, I knew long before the election. I was invited to this position more than once, but I was far from this and therefore I did not agree to participate in such elections for several years. When the proposal came from the Russian Musical Union, which also decided to take us under its organizational and financial wing, I realized that the matter was becoming serious and the Union of Composers could reach a new level. Immediately agreed to run for the post of chairman of the Union of Composers of Russia. A conference was held which brought together representatives of regional creative organizations, where they elected me.

– What is your personal history of relations with the Union of Composers?

– At first everything was easy. In 1968, after graduating from the Conservatory, I became a member of the Union of Composers. My teacher Aram Ilyich Khachaturian and Tikhon Nikolaevich Khrennikov, who warmly treated me from my very childhood, accepted me into the Union. Everything developed remarkably: I participated in contests of young composers, became a laureate for my compositions – the concert capriccio Skomorokh, overtures for the holiday. But as soon as I became interested in rock music and wrote the rock opera “The Star and Death of Joaquin Mureta”, the Union of Composers abruptly turned away from me and prevented me from participating in any of his life. Then ideologically it prevailed the Central Committee of the party. It got to extremes: they dismissed a female musicologist who wrote her dissertation on opera. There was no persecution against me, there was an instruction not to cooperate with me. But I continued to write, work. He waited until the Soviet power ended, and with it the Union of Composers fell into a very difficult situation – no one needed him. Hard times have come for composers. They continued throughout the 1990s, the 2000s, and continue, unfortunately, to this day.

– How does the current Union differ from the Union of Composers of the USSR? What was good about the organization that is better now?

– My personal history with the Composers Union began when, when I was 14 years old, my father went to Tikhon Nikolayevich Khrennikov and showed my notes. He saw them, said: “A talented boy,” immediately signed a petition to the chairman of the executive committee of the Moscow Council with a request to allocate an apartment. We then lived in a communal ten meters away. Imagine how powerful the Union of Composers was then? He built houses, had his cooperatives.

The state provided a living space and benefits. There was the Muzfond, which ordered works to composers, received deductions from the performance of all Russian music – Glinka, Tchaikovsky, Mussorgsky, Rachmaninoff. The Union Publishing House published new music, works by contemporary composers were performed at plenary meetings, congresses, and festivals. There were wonderful houses of creativity. The composer felt in caring hands – there was an environment in which one could live and be engaged in creative work.

Now the complete opposite is neither control nor support. Most of the property of the Union, given to him by the state, has disappeared, is sold out. My familiar composers in one voice say: “Either continue to work, making ends meet, or throw creativity.” Every year the Conservatory produces a lot of talented musicians who go into this world and do not find use for their talents. We are losing one of the most important globally Russian music schools, which, along with Germany, Italy and France, was at the forefront of classical music. We must not allow this to happen.

– If you continue to compare the past and present: what is the difference between music itself? Once you compared the musical with “champagne with cakes”, and the rock opera with “vodka with black bread”. If you could describe briefly the classical music of the XX and XXI centuries, what two combinations would you describe them?

– This is a very, very serious matter, since everything is connected with the development of society. For me, the 19th century is still the epoch of great creation, the 20th century is the epoch of destruction of the foundations when all were revolutionaries – mediocre or ingenious. Stravinsky, Prokofiev destroyed the foundations, not to mention the new classics – Arnold Schoenberg, Anton Webern, Alban Berg. After destruction, a decline is usually observed. And as soon as the century of revolutions, the great wars with colossal sacrifices died down, the 21st century came – the era of degradation, discord in everything. But at the same time, as the dialectic taught us, in this chaos a new level is born, an update is taking place. I can not imagine Russia in the conditions of spiritual degradation. This was already once in the conditions of Bolshevism, the second time we do not need it. We must be spiritually reborn and set an example to the world.